It's always hard to post images after interviews with

Pulitzer Prize winners. I'll

never have anything on hold to post that would compare to their work. Primarily because I tend to take "happy" photos while most competition award-winning photos aren't happy.

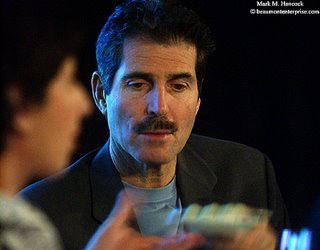

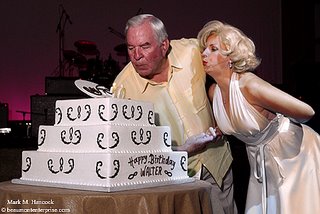

So, I'll do the opposite. I'll post some "making lemonade," "stone soup" or "silk purse" images. These are images from less-than-coveted assignments. Look at the image and then ask yourself about the assignment and why it was assigned.

Keep in mind that each photo assignment costs a newspapers anywhere from $200 to $400 or more (include PJ time, benefits, mileage, etc...). So, if the assignment is weak - for whatever reason - it cost the company the same amount as a quality assignment.

In all cases, PJs must remember the subjects aren't responsible for the assignment (most of the time). They are often simply thrilled they'll be in the newspaper. So, as both of this year's prize winners noted, every assignment deserves a PJ's full attention and ability. Each shoot must be done as well as possible. This work ethic shows the PJ's professionalism and creates good will with subjects and readers alike.

During the monthly meetings in Dallas, a standing joke was to say, "You get all the good assignments," to the senior PJs who squeezed coal into a diamond. It was an understood complement to the PJs' ability to do well under challenging conditions.

The nifty side effect of this experiment is that until I have an obviously cool assignment, both of you (regular blog readers) will think I'm making good photos out of these assignments, rather than bad photos at great assignments. :-)

Enough for now,